05 Nov Everything Inc.

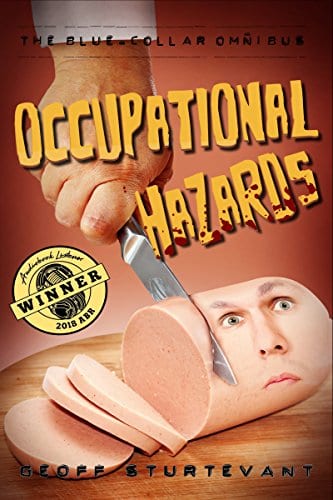

“Everything Inc.”

Written by Geoff SturtevantEdited by Craig Groshek

Thumbnail Art by Craig Groshek

Narrated by N/A

Copyright Statement: Unless explicitly stated, all stories published on CreepypastaStories.com are the property of (and under copyright to) their respective authors, and may not be narrated or performed, adapted to film, television or audio mediums, republished in a print or electronic book, reposted on any other website, blog, or online platform, or otherwise monetized without the express written consent of its author(s).

🎧 Available Audio Adaptations: None Available

⏰ ESTIMATED READING TIME — 78 minutes

If you want to know just how unimportant you are, get a job at the biggest company you can. The bigger the outfit, the smaller the cog you’ll be in that cascading clockwork that makes the thing move.

You’d be more significant as the sole proprietor of a banana stand than you would at any capacity with Everything Inc. At Everything Inc., you’re as good as dirt.

Thinking back, it’s interesting to remember those red brick strip malls that used to be the center of every town. Always L-shaped, a supermarket to one side, a bank, a drug store, a pizzeria, a Chinese place, and a handful of little mom ’n pop shops that flavored the town and sponsored the youth’s sports teams. I remember hanging out at the Drug Fair as a kid; the keystone of my own town’s mall, playing video games with my friends in the little arcade nook in the back, near the pharmacy. The worn, waxy floor tiles collecting grime and black gum in their cracks, like a premonition of the things to come. The drugstore’s days were numbered, and so were all the others’.

Funny to recall the little excuses for businesses that used to inhabit these crumbling brick buildings. A stationery store, a hardware spot, even a gift shop. A gift shop, for God’s sake. But keep in mind, there was also a place you could rent VHS tapes. And if one of them decided to unravel in your pop-up VCR player, you were out a good sixty-five bucks to replace it. I’m talking prehistoric times here.

Funnier still, the fact that no one expected the inevitable. The first casualties, of course, were the niche, little shops. One by one, the windows went dark; black storefronts, like missing teeth. For us kids, the old Drug Fair was suddenly not such the place to be.

Even the mighty department stores; the knees and elbows of the big, indoor shopping malls, beat their retreat. The chandeliers hung dark behind the doors. Papered-over windows, like white flags of surrender.

It fed on the shops. Fed on the shopping malls; steadily snatched up the franchises, leaving big, woodwind instruments of the buildings. Fed on the Alpha companies: the Walmarts, the Targets, the Kmarts; just consuming everything in its path. In the end it settled there, an immense, bloated monstrosity; bigger than its sum of victims, bigger than business, bigger even than the law. Spawning buildings to contain kingdoms; buildings to block out the sun. The aptly-named Everything Inc. Such a logical conclusion, it’s a laugh that no one saw the snowball rolling. Give two people in a room a buck apiece, they say, and in an hour, one of the guys will have both of them.

Well, Everything took it all. Everything was everything. If there was a mission statement, it was this: To become everything, including, but not limited to: absolutely everything. But of course, mission statements were not so important anymore.

Taking the train out to Enterprise City, the staggered roofline of Everything Inc. Headquarters lifted slowly from the horizon like a square-shaped mountain, too big for the eyes to completely drink in. Marginalizing the sky. Blocking out the heavens.

The hive towers stood trackside like great guardians. Thousands of tiny tenements housing the 50,000 supposed employees of Everything Inc. Meager accommodations, but it beat being in the streets. These rooms were what we train riders were after; when you just couldn’t swing it in the outside world, four walls at all made a merciful place to hang your head.

“What say, doggie?” came a bayou drawl from across the aisle.

I turned to see a man reclined cross-legged in a sharp hide overcoat. A wagering grin on his dimpled face. He held a well-read book closed on his thigh under a fingerless glove. Solaris, by Stanislaw. I’d read it myself a long time ago.

“Got a job lined up?” he asked.

“Haven’t been hired yet,” I said. “Figured I’d hoof it out here and see what happens. Got nothing back there.” I pointed my thumb at the back of the train. Back towards the coast.

“No one does,” he said. He gestured west with the arch of an eyebrow. “You’d be lucky to dig up a turnip back there. Nowhere to go but thataway. Forward on, doggie.”

“How about you?” I asked. “Got a job?”

“Hoofin’ it out, such as you say. Same as you.” He smiled amiably, tilting back his trucker’s cap. “Somebody told me once, whatever you’re chasing, you gotta chase after it, even if you don’t know what the hell it is.”

“I suppose that may or may not be good advice,” I said.

He grinned. “Sure, well the guy was drunk who told it to me. What kind of job are you looking to do?”

“I’m just trying not to set the bar too high. Not this time around.”

“Now that’s no way to look at things.” He stuck out a gloved hand. “I’m Dan,” he said, “and I’m pleased to meet you.”

“I’m Paul.” We shook. Maybe it was no way to look at things. But at the time, you could hardly blame me.

This time around was a kind of backup plan for me, my final failsafe. I’d always tried to imagine a backup plan for myself, just in case the whole enchilada fell apart, you know? Still, I never really imagined I would need it, not until the enchilada went ahead and did just that. Failure, I’ve found, will flank you from all sides. It grows around you like some sort of imminent bacteria.

Back in my college days I knew a lot of guys from South America living up here, washing dishes, bussing tables, stuff like that. They lived by the bunch, stuffing themselves into little apartments, splitting the rent and costs of living. They worked like ants, piling up all the tax-free cash they could, and wired it all down home. By the time they made their way back, they had enough saved up to get by with a part-time job selling bananas. A fellow once showed me a picture of the beach house they were building for him down there. I could hardly believe it. Looked bigger than what most families could afford up here.

So that was Plan-B, to save up a few bucks and move down to where the money was still worth something; be some big-shot gringo in some third-world town. But no loophole stays open forever; these days, houses down there’ll run you more than what they cost up here. I missed the boat, so to speak. But who isn’t to say the big ellipsis of failure might swallow them up too? Swallow up the circle of the earth? An object in motion tends to stay in motion, doesn’t it? So, logically, no one is safe in the Einsteinian Universe.

Well, if you can’t beat ‘em, might as well join ‘em. The sovereign social experiment turned juggernaut, Enterprise City, was the only real backup plan you could hope for these days. A place to slink off to and lick your wounds once life got through mauling you. Things were bad, but there was always Enterprise, granted you had enough scratch left for the train fare. There was always the front stoop of Everything Inc., where you could go prostrate yourself in front of and beg to be given a job and a place to live, granted you could spare the pride. And there was a fair chance they’d let you in, too. Because it was cheaper to put you up than to bury your desiccated corpse in the Mojave.

Smog on the horizon, sepia in the artificial light of the cityscape. The skeleton of a long-dead Vegas, colonized by some prolific fungus. This symbiotic organism that both fed and fed on it’s people. Everything Incorporated.

I watched through the window, the marker lights of the freight cars doubling by as they sped out of Enterprise and into the parched wastes. Hauling in barge loads of shipping containers, Chinese symbols flitting by in the guidelights. Carrying out everything, literally, Everything-brand everything, to anywhere anything was needed, tracing twisted maps across the country and beyond, like unbridled blood poisoning.

We wheezed to a stop at Enterprise Station, traincars careening by the dozen from the depot. Benches of bundled-up travelers in attitudes of exhaustion.

I felt a hand on my shoulder. “I take it you’ve never been here?” said Dan.

“No.”

“Follow me, then.”

“You’ve been?”

He nodded once, half-grinning. “I came, I saw, I left. Then, I was conquered. Now I’m back.”

The lights illuminated the steamy smog into a kind of fabricated daylight. I bought a styrofoam cup of coffee from a sleepy bodega vendor on the platform for two dollars. The sight of real money rather than a credit voucher seemed to perk him up. He put the bills directly into his pocket. The coffee was burnt and bitter, but the cup warmed my fingertips.

“What happened the last time you were here?” I asked.

“I worked at Everything two years,” he said. “I thought I’d take another stab at the free world. The grass is always greener, ain’t it?” He sniffled, wiped his nose on his cuff. “Thought I’d scratch together a living doing this and that. Friend of mine had a pickup truck. Collected scrap metal, moved stuff, that kind of thing. And when the truck ate it… I swear, the minute you get up on your feet, the world’ll just flat kick you back on your ass.”

“So you gave up?”

“Well, not right away. But once I had enough to fix the truck, who do you think I had to pay for it?”

“Everything Inc.”

“Boom. That’s when it hit me. I’m busting my hump, and now I’m paying Everything in dollars for what used to cost me credits. I just can’t swallow it, doggie. I ducked and ran. And here I am.”

I nodded. “It’s just no use.”

“Not that I’ve found. The way they’ve got things, it’s only a matter of time ’til you’re hightailing it back here.”

I took a last sip and dropped the coffee in a passing wastebasket. It wasn’t worth the warmth to hold it.

We walked off the platforms into the terminal station. Electronic billboards lining the walls, flashing advertisements for Everything products and services. A show of pride at most; there was no need to advertise any of it. If there was something you needed, I mean anything at all, it was coming from Everything Inc. It was Everything or nothing.

Up on the veranda we caught a shuttle to Receiving, one of the last places in Enterprise that would officially accept my dollars as payment. Street-side as we went, the nighttime crews out collecting garbage, shuttling it to the methane plant. Enterprise Police propped lazily against signposts. The occasional clusters of bundled-up homeless huddled by a staircase or a dumpster, braving the cold vacuum of the desert night.

“Some people’ll take the open cold over a warm night in the hive,” Dan said of the homeless. “Maybe I would have too once. Maybe in my twenties. But not now.”

“I just don’t get it,” I said.

He understood what I meant. Enterprise was where you came to get your wet ass under a roof. How could you end up homeless in a place like this?

“Lots of people fuck up out there,” Dan said. “Some people’ll do it in here too. Some people’ll fuck up anywhere, just give ‘em a place to fuck up, and they’ll go ahead and do it.”

I’d been under the impression that everyone here had enough to get by. Or at least enough to sleep indoors.

“Life is cheap here, but it’s not free,” Dan went on. “Out there, it costs money. Here, the currency is pride. And speak of the devil…”

He pointed at a black man shuffling under a streetlight. His eyes were glassy in the yellow glow. “That guy right there, see him? There’s a fella that couldn’t cough up the pride.”

“He doesn’t look like he has any to spare,” I said.

“Old Dave, proudest sonofabitch you’ll ever meet. Crazy as a shithouse rat, but proud as they come.”

“You know the guy?”

“Used to. Glad to see he’s still got his feet under him. Crazy bastard. At least he’s still above ground.”

I watched the man disappear in the rear windows of the shuttle. The hives loomed behind, high and dark in the artificial twilight glow. The stars I’d seen only twenty miles back had all been snuffed out. With them, all past perspectives and future expectations.

“We stamped household goods,” Dan said. “That’s all we did. Fourteen hours, stamping, then it’s back to the hive, no funny business. Well, he started sneaking out at night, couldn’t stand the rules. Reckless. You get caught out after curfew, you get fined. Get caught three times and you’re out on your ass. By then, you could never pay the fine anyway; you only get enough to live in the first place. The guy had some bad habits, probably still does, so he lost his place after fine-one. And Bob’s your uncle, homeless in Enterprise.”

“But he’s still got his pride,” I said.

“That’s all he’s got. Besides those habits. There’s a way to do your unsavories here, you just gotta do it quietly. Dave, he just plumb held his hat on and ran.”

“Well,” I said, “whatever you’re chasing, you gotta chase after it…”

He chuckled. “Now that I think about it, Paulie, he might’ve been the drunk prick who told that to me.”

I grinned. It was the first grin I’d allowed in a long time. I think it was also the first time anyone had called me Paulie.

Paulie, Paulo, the Paul man, one Paul to rule them all. Any variation on my name you could think of, Dan thought of it first.

It was 1:30 a.m. by the time we reached the receiving terminal to join the mass of free-world refugees. 2:30 by the time we wound through the desperate lines to approach the admissions officer. By now I was so tired, I wished I’d hung on to that cup of coffee. Dan, too, seemed to be teetering on the brink. The size of the place alone seemed to suck the life out of you.

“I’m about ready to get horizontal,” Dan said.

“Gotta get admitted first.” I’d heard it took hours. Days, sometimes.

“Nah,” he said. “Leave it to me.”

“Next.”

We approached the counter together. I set my heavy bag down on the floor.

“Applying for admittance?”

“We’re pre-approved,” Dan said. I glanced at him. This strange guy who seemed to know his way around.

“Paperwork?”

Dan took an envelope from his jacket pocket, unfolded two letters and handed them to her. She examined them briefly, one after another, then handed them back.

“Hang onto those,” she said. “Here are your room vouchers, bring those to the boarding desk.”

“Thank you ma’am,” Dan said, taking the vouchers.

“Thanks,” I said. And we left.

I glanced back at the winding lines, pitying those still waiting to apply for admittance. “How’d you manage that?”

“Oh, the letters? Gotta pull some tails to get ahead in the rat race.”

I wasn’t about to look a gift-horse in the mouth. He’d just saved me that whole prostration at the doorstep business; it didn’t matter how he’d done it. I was just lucky he had. For the first time of many to come, it occurred to me how helpless I was on my own. “Thanks,” I said. “A lot.”

“Don’t mention it,” he said. “Let’s go find us some beds.”

Arriving at the hive, the group of newcomers were arranged in an orientation room for an explanation of the bylaws, delivered by a short video starring our benevolent president, Len Carter. Yawning, we signed a number of forms certifying that we understood and agreed to the rules. The final form, the most important one of all, we were told, was the “Pledge of Community.”

I pledge to be put to my best use in the interests of Everything Inc. and the Sovereign State of Enterprise. Signed, Paul Harper.

With that, it was official.

Hive bylaws were designed so that you wouldn’t even consider violating the status quo. The uniformity officers roamed the hallways checking for anything out of the ordinary—decorations, colors, door hardware, anything at all that suggested individuality before uniformity. On the way there, Dan had told me about the oppressive fines dealt out for everything from shoes outside the doors to the smell of whatever you were cooking inside. After only minutes there, I could sense the tension, everyone keeping to themselves, trying desperately not to stir the air.

Dan and I were issued adjacent rooms. Rooms practically the size of walk-in closets. Little beds, kitchen nooks, tiny bathrooms and tinier closets. Across from the bed was a little TV screen built into the wall. I set down my bag and opened the sink faucet to little more than a drip. I washed my hands and face, glancing eagerly at the bed in the tiny shaving mirror there. When I crawled under the thin cover, my feet hung off the end of the mattress, but that was alright. It was the first real bed I’d been in in days.

The building was quiet as a graveyard. Lying in silence, a twinge of loneliness settled in my stomach. It occurred to me crisply now, in the perfect quiet and in my unguarded exhaustion, where I was and what I had done. I’d left it all behind, the precious and the broken alike. I’d truly crawled back into my childhood bed.

I tried lying on my side, but the thoughts persisted. You weren’t chasing after anything when you got on that train, were you, Paul? Not like Dan had said. No, you were running. You’re a failure. And now you’re here, with your little feet hanging off the edge of a mattress. No matter how you tried, you just couldn’t swing it, could you?

It was nearly 4:00 a.m. by the time rumination gave in to exhaustion and I dozed off into an uneasy sleep. Dreams of hiding, dreams of failure, dreams of finality.

I woke to a knock at the door. The sun was full in the little square window, casting three black shadows of the suicide bars across the white bedsheets. The clock said 9:45. I’d slept a good six hours. I swung my legs off the bed and went for the door. It was Dan.

“How ‘bout some breakfast, doggie?” He had that same grin on his face, only clean-shaven now with his wet hair freshly combed back. He had on overalls over a button-down shirt, cuffs rolled up to the elbows of his hairy arms.

“I’m starving,” I said. I was, now that I’d thought of it.

The ephemeral gloom I’d felt the night before had abated for the time being. Maybe some of it was the freshness of a new morning. But the fact of Dan waiting there, leaning goofily against my doorframe waiting for me to get dressed, I suspect, was most of it. I might have felt lonely, but I wasn’t alone. Not altogether.

We took the stairs down to the first floor. The breakfast bar was down to its dregs, but the look of food laid out for the taking was a relative thrill. Lodging had included fifty credits with our pre-approved vouchers, enough to feed us for a day or two, and we ate what we both agreed was the biggest meal we’d had in months. Not so fresh anymore, but grand regardless. Everything-brand eggs, toast, cereal, and a couple cups of Everything-brand coffee. “Gotta get tanked-up for the placement interviews,” Dan said. And we certainly did. My shriveled stomach was packed like a baseball. It felt good. Last night’s emotions all tucked into the pending file for the time being. I was here, and I had to make the best of it.

We walked and chatted, boarded a shuttle at 11:00 and walked into Placement fifteen minutes later. I recognized a few of the passengers from the night before, everyone fresh, well-fed, and ready to start anew.

“What’re you aiming for?” asked Dan.

“Hoping to get a job at the power plant,” I said. I’d always known the sovereign city had a huge gas turbine power plant and made its own gas and electricity. Unusual technology, supposedly, but I did know my way around a power plant, at least in several capacities. Enterprise was supposed to be tops in resource technology; the only one they couldn’t manage themselves was water, although I’d heard they were well on their way to figuring that out too. And when they did, President Carter had promised America, it would mean even more jobs for the destitute public.

“I never considered that,” Dan said. “When you think of working for Everything, you usually think of making stuff. Putting stuff together, that kind of shit.”

“It’s what I know,” I said. “At least some of it. Might as well hold up the Pledge of Usefulness.”

“The Pledge of Community,” Dan said. “But that’s close enough.”

Dan and I were waiting at the front of the line when one of the applicants receiving his placement began to raise his voice.

“I’ve got a Masters Degree,” he said.

“Congratulations, Mr. Simmons,” said the placement officer.

“I didn’t do all that studying, all that work, to wield a mop.”

“Mr. Simmons, there are no jobs for radio engineers here. Your practical aptitude assessments have you placed in the custodial department.”

“Come on, there has to be something. I’ll never be able to live on the salary of a janitor.”

Dan nudged me with a knowing elbow.

“We all get by on the salary of a janitor, Mr. Simmons,” said the placement officer. “We get by, so will you.”

“Remember what I said about pride?” Dan asked. “This guy’s gonna have a hard time paying the bill.”

I nodded.

Dan went ahead and took Mr. Simmons’s place. Soon after, a spot opened up for me. The placement officer, a stiff, young man, had me fill out a brief questionnaire on the computer. I indicated wherever I could that my experience was with a power company, and that’s where I thought I’d be the most useful. I hadn’t done a whole lot: basic electrical, maintenance, etc., but it was an environment I was familiar enough with. Most of all, though, I didn’t want to get stuck “putting stuff together,” like Dan had said. I really did want to make myself useful. I wanted to feel useful again.

After I’d completed the questionnaire, the placement officer fed it into the system and examined the results.

“Looks like they’ve got you a position in production.”

“I was hoping for the power plant,” I said, my stomach sinking. “That’s where I’d be the best off, I think.”

He glanced up at me from the screen. “The plant is off-limits to employees,” he said. “We’ve got you in production.”

“Off-limits to employees?” I asked. “Don’t employees work there to begin with?”

Something in his eyes let me know he didn’t care to discuss it. It wasn’t his decision where I worked. The computer decided where I worked, and the decision was final. I could take it or leave it, meaning I could take it, or kiss my apartment goodbye and shove off. They didn’t need me as much as I needed them. They didn’t need me at all.

“Alright,” I said. “It’s no problem, just curious.”

“The job is line assembly. You’ll receive all the necessary training, starting tomorrow. Report at 7:00 a.m. sharp to building 84-A. Follow the signs to the training desk. Your supervisor is Oris Smith.”

He printed out the paperwork, stapled it, and handed it back to me along with my voucher. “I’ve validated your lodging voucher for another day. Once you’ve completed training, have your supervisor sign this form and return it to Lodging for employee verification.”

I accepted the forms, trying not to appear disappointed. Line assembly. I’d be putting stuff together after all. I just couldn’t picture myself doing such paltry work.

“Any chance in the future I might get into the plant?”

He shook his head. “Only very specific personnel are allowed into the plant. It’s not going to happen.”

Dan was waiting for me outside the placement center. “Where’d they put you?” he asked.

“Production. No luck with the plant.”

He smiled. “84-A?”

“Yeah,” I said. “How’d you guess?”

“That’s where they sent me. I told ‘em the same thing you did. Hoping we’d both get in the plant.”

“You said you had electrical experience?”

“Sure, why not?”

I chuckled. “Do you?”

“Let me tell you something, doggie…” He put his heavy arm over my shoulder as we walked back to the shuttle station. “There’s no job you can’t do here. It’s all easy shit. I just don’t want to do it alone. Being a slave is one thing. Being a slave alone, that’s the pits.”

When I was a young man, working restaurants, delivering pizza, etcetera, I’d think a lot about the money I was racking up while I worked. I’d mentally tally my tips, trying to figure out how much I’d made so far, how much I’d averaged per-hour, and how much I could save by the end of the week. Money was novel back then, back when you could tuck some of it away, save a little bit. When you’re young, being broke is the norm. Anything above that is pure wealth.

Kids change everything, of course. If you’ve got kids, your pockets are empty. There’s no money to be saved, so the novelty is nil. Your base of operations is having enough money. Enough is plenty; the idea of a surplus is plain silliness.

Fail to make enough, though, and you’re in loser territory. And there’s no excuse by then; you can’t blame your parents, you can’t blame your situation, your race, your gender, your place in society. It doesn’t even matter that there are no jobs to begin with. It doesn’t matter that food is so expensive, that housing is so expensive. You can’t provide, you can’t pull your weight, and now you’re a failure. It’s a bad feeling. I know the feeling well.

Everything Inc. moves the baseline back to where it was when you were young. Money still lacks its former novelty, but at least the amount you’ve got will keep you clothed and fed. It’s like being back in your parents’ house; like regressing into comfortable, complacent childhood. Not a challenge to be had. Not the proudest place for a man to be either, but like Dan said, the pride is the door-charge. For a grown man who’s already been through the meat grinder, who’s already lost his house, his family, and who-knows-what-else, it’s a tough carrot to cough up. That might be the hardest part of the job.

The rest of the job is easy. Painfully easy. The necessary training, as the placement officer had put it, could hardly be considered training, and the job could hardly be considered work. Dan and I stood across from each other on the assembly line, repetitively performing our trivial duties. For me, I inserted a three-point pin into a three-hole plug. Pin goes into the plug, and I hit the red “done” button, adding one success to my hourly tally. The pieces moved on to my left, where Jack Johnson, a spiky-haired fellow in his mid-forties, wraps a strip of electrical tape around a group of wires, then hits the “done” button. Then on to Ronnie, with his sausage-fingers, who fiddles with a plastic hood until it clicks into place, “done” button. Then around the corner and on to Dan, whose job was to touch an alligator clamp to a screw and press a button. If the led-light lights properly, he sends it on down the line and hits the “done” button. If it doesn’t, he slides it back across to me, where I check to see if it’s plugged in right, then I send it back up to Jack to recheck his part, on to Ronnie, and so on.

The job was so simple, you could do it without using your brain. As long as you kept hitting that “done” button enough times per-hour, no one questioned your performance. At times we were quiet, just working like ants, each doing our little part. Other times the chat would start up and we’d be joking around, our hands working independently, leaving us free to bullshit.

We all shared our backgrounds, problems, failures, etcetera. As much as we were comfortable sharing, anyway. Dan revealed that he’d always wanted to be a writer, that he used to love to write fiction. He also told stories about his last run at Everything and how he’d had another go at the outside. It turned out Jack, who apparently hated being called JJ, had made a similar second attempt at the free world. “The grass is always greener,” Jack had said. “And really, it ain’t. I’ve been back and forth enough, believe me. You get fucked either way, just in different positions.” Dan agreed—the grass isn’t any greener out there. It was scorched earth out there. You couldn’t dig yourself up a turnip out there. “You’d sooner dig yourself up a dollar,” I said.

“I hear ya,” said Ronnie. He said that after almost everything I said.

“You’d sooner dig yourself up a nice new shovel,” said Dan.

Back at my room after a long shift, the loneliness seeped back into my thoughts. The walls seemed closer than ever. I had this overwhelming urge to kick my door off the hinges. Not even to leave, but just to have that open space in my doorway to ease the close-quarters cramp. The second it crossed my mind, I heard the boots of the uniformity officer clumping by. Having your door open after curfew would earn you a nasty fine, leaving you scratching for weeks before you were back up to speed. Claustrophobia or not, it was prohibitively expensive to break the rules.

The clumps continued down the hall and around the corner and then they were gone. I allowed myself a moment to feel the childish resentment of being locked in my bedroom. The point of these rules seemed less about uniformity than about subtracting one’s dignity. Too much dignity would be a bane to a place like this. You had to be a genuinely beaten man to allow yourself to be locked in your bedroom after dark. A few years ago, I’d never have been ready for it. But now, here I was. I was that guy.

I sat down and yanked the laces on my boots and kicked them off onto the floor.

Knock knock…

I thought the noise had been my boots landing at first, but then I heard the knocking again.

Knock knock knock…

I listened. The noise was coming from the closet.

I stood up. “Someone in there?”

Knock knock knock…

I walked over and opened the closet door. The knocking was coming from the other side of the wall. I leaned in and knocked back.

“Heya doggie,” came the muffled response from the adjacent room.

“Dan?”

“You sleeping?”

“No, I’m up.”

“I feel like a kid sent to his room,” he said.

“It’s like you’ve been reading my mind.”

“How ‘bout a little mischief?” he asked.

“What do you mean by that?”

“Let’s make a little hole.”

“A hole?”

“Yeah.”

“You mean in the wall?”

“Yeah.”

“What? We can’t do that!”

“Keep quiet, they’ll hear us.”

“Sorry,” I said.

“That’s why I wanna make a hole. We can chat through it. Without being loud.”

“We’ll get tossed in the street, Dan.”

“I’m in my closet too, doggie. There’s no way for ‘em to find out.”

I thought about that. The closets were the one place off-limits to the inspectors. It was the only place in the room you could lock up your personal belongings. Theoretically, you could do whatever you wanted in there, and it was your own, personal business.

“I don’t know, Dan.”

“Just hold on a minute…”

I heard some scratching around behind there. Moments later, the blade of a long screwdriver thunked through my side of the wall. A little burst of dust hung in the air.

“Lucky it’s just sheetrock,” I heard him say. And he began winding the screwdriver around, widening the hole.

“This is bad,” I said.

“Nothing back here, no wires, plumbing, nothing. Just a couple sheets of wallboard. Easy as pie.”

Of course that wasn’t what I was afraid of. I was afraid of getting fired, of failing yet again. This was my only backup plan. If I’d run all the way to Enterprise only to become a failure again, I was truly finished.

The screwdriver withdrew, leaving a hole about the width of a silver dollar.

“Not too dusty, I hope,” Dan said.

“This is a bad idea, Dan.”

“Hear you much easier now.”

“Seriously, this is not good…”

The boots were approaching again. We both stood silently waiting for the officer to pass the other way down the hallway.

When he had gone, Dan said: “Well, what’re we drinking?”

“Very funny,” I said.

“Don’t worry, doggie, I’m buying. Hold on just a minute.”

The screwdriver came back through the wall.

“No, Dan, I hear you fine,” I said. “That’s it, that’s plenty.”

“Just another inch,” he said. “Keep your ears open for boots.”

I stood back. Rivulets of dust poured from the widening hole onto the carpet. I was faintly nauseated now. If we got caught, I could say I had nothing to do with it. My neighbor was crazy, that’s all it was. He went nuts and started stabbing the wall. It would be the truth, too. Dan was obviously losing his mind.

But there was no stopping him. Resigned, I went and put my ear against the front door. No one nearby. The uniformity officer must have been pretty well across the building. And on the positive side, it was highly unlikely anyone would complain if they heard the noise. The tenants regarded the staff more like predators than security.

The scratching finally stopped. “You there, doggie?”

His voice was clear now, almost like he was right there in my room. I went back to the closet. The hole was significantly larger now.

“Oh God,” I said.

“Success,” said Dan.

A moment later, a dark brown cylinder protruded from the wall.

“Can you get ahold of it?” he asked.

The moment I touched it, I knew exactly what it was. It was a cold, glass beer bottle. With a thwunk, I pulled it through the hole.

“Where did you get this?”

“Guy I know from last time through. Snuck up a twelver.”

“How’d you get it past security?” There was a security guard at the entrance that checked everyone’s bags, and alcohol was one of the many prohibited items.

“I gave the guard a few.”

“You bribed him?”

“He might be security, but he’s still a man. And men like beer, don’t they?”

A bottle opener presented itself through the hole. I took it. With a beer in one hand and an opener in the other, I was suddenly less dubious. After all, he was right. Men love beer, and I was no exception.

“It’s a tough system,” said Dan. “But every system’s got weaknesses. Just gotta find the soft spots.” He wagged a finger through the hole he’d made in the wall. I had to grin.

After a cheap breakfast of Everything-brand cereal and Everything-brand eggs, we were shuttled off to 84-A, greeted by the acrid chemical odor of plastic fumes. We filed out of the cars and onto the platform.

Vendors in their bodegas sleepily offered us coffees for two credits apiece. The small cup I’d had at breakfast wasn’t doing the trick, not after the four beers I’d had last night with Dan. I bought a coffee, dark and oily in a paper cup, and signed my name and pin to authorize a debit to my account. Curious, I hung behind at the coffee stand a minute.

“How do you do here?” I asked the man, a haggard, bearded fellow in his sixties.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Money-wise,” I said. “Not to be nosy.”

“You must be new.”

“Yeah, I’m new.”

He stroked his scraggly beard. “Same as you, one way or another. What do you do?”

“Production,” I said.

“What do you get? Money-wise.”

“2000 a month.”

“Alright, so I sell maybe a hundred cups a day. That’s two hundred credits, seven days a week. That’s 5,600 credits.”

I practically recoiled at the thought of it. That was 3,600 more than I was making in production, what was I doing there? He seemed to pick up on the entrepreneurial notions sailing through my mind.

“Everything brand coffee costs me about 1000 a month. Renting the space runs me another 1500.”

I did the math. “Alright, so you still take home 1,100 more credits than I do.”

“Then the so-called affluence tax. There’s another 750 gone.”

“Affluence tax?”

“They whack you with that one at 2,600 after fees. Brings my take-home down to 2,350.”

“Still beats my salary,” I said.

“How many days you work?” he asked.

“Six.”

“And I work seven,” he said. “So unless your time’s not worth anything, you’re making more per-hour than I am.”

He was right. Eight extra hours a week he worked, that’s thirty-two more hours a month. For a measly 350 credits. It wasn’t even close to worth it.

I walked away with more than just a cup of coffee—talk about waking up. So what could you possibly do here to get ahead? All you could make was just the amount you needed. All you could afford were the products Everything provided at discount prices. Paycheck to paycheck, that was the only way you could live.

I sighed, dissipating the steam of my coffee cup. Well… at least you could live.

We worked all day in the plasticine steam, (which did little to settle my hangover) assembling parts for Everything’s line of children’s toys. Little plastic houses, with little plastic doors. In our usual spots, I had the easiest task of all—I plugged the pin into the jack. DONE. Jack screwed together the little working doorbells you fastened next to the doors. Easy enough. A little circuit board, a battery, and a switch-button. He’d heat up the beads on the switch wires with a soldering iron and drop on the leads. By the time the assembly reached Dan, he pressed the button to make sure it went “ding-dong,” and if it did, “done” button. The next guy along fixed it into the door. Just like that. All day long.

“So check it out,” said Jack. “How many of these things are we cranking out an hour?”

“Ten?” I guessed.

“About that. And we’re making 8.33 an hour, four of us, to build ten of ‘em. That means, excluding materials, it costs Everything around three and a quarter to get one of these things built.”

He looked at Ronnie, installing the battery fastener. “Ronnie, how much you figure the raw materials to be?”

“I dunno, JJ…maybe five creds?

“Sounds about right. And don’t call me that. And what’s the retail, Ronnie?”

“Twenty-nine ninety-five, JJ.”

“Ding dong,” went Dan.

“And with our employee discount?” I asked.

“You thinking about having some kids, Paulie? In a place like this?”

“Just curious.”

“Half-price,” said Ronnie. Fifteen, give or take.”

“Fifteen,” said Jack. “Costs ‘em about eight and a quarter. Hundred-percent markup.”

“Some discount,” Ronnie said. “Some great act of altruism.”

“Altru-what?”

“There’s just no way to make money,” I said. “It’s like the whole thing’s designed to keep you running in place. Enough to get by, but that’s it.”

“That’s the idea,” said Jack. “And even if you could, what’re you gonna do, stick credits under your mattress? It just don’t work.”

“Why would you do that?” said a new guy down the line. “Aren’t they safe in your account?”

Both Jack and Ronnie chuckled at that. “You’re green as a baby twig,” Jack said.

“Too much in your account,” Ronnie said, “and they’ll whack you with the tax-axe. A credit over 2,600 at any time, and you get nailed for 750. I’ve seen it happen.”

“I heard about this,” I said. “Just this morning, from a coffee guy.”

“The coffee guys get it bad,” Jack said. “Cold months like this, they make a killing, but they cut ‘em right back down to size. 3,200, and they whack ‘em with a thousand-credit fee. 4,000, and it’s a 1,500 credit fee. And it just goes up.”

“Boom,” said Dan. “No matter how hard you try, we all walk home with the same little bag of shells.”

Twelve hours, we were at it. By the time I got back to the hive, my legs were wet cardboard. The guys had all told me I’d get used to it, and I hoped they were right. If they were, it couldn’t happen soon enough.

Taking a break on the way up the stairwell, a fire escape map caught my eye. I leaned on the railing a minute and studied it.

YOU ARE HERE, it said. It pictured an example of all 20 floors of the building. The hives were all colossal L-shapes, like the old strip malls of my youth, only much, much bigger. Leaning in closely, I counted up the units. Each floor contained roughly 200 rooms like mine and Dan’s. I also noted the extra-small units I’d heard about in the crook of the L, by the laundry and storage/utility units, and at the ends of the building. There were 20 of those per-floor. So 220 units per floor, times 20, was 4,400 units per building. As big as some towns.

Up on my floor, I glanced down the long hallway, full of doors. Everything perfectly uniform and grimly quiet. Strange to imagine there were so many people behind these doors, like sleeping bees in a colossal honeycomb.

The job so mechanical, the hours so long, and everything so uniform, the days seemed to amalgamate into single, week-long shifts. If it weren’t for Dan and me gathering in our closets for beer most nights, the tedium would have been intolerable. I mentioned coughing up the pride was the hardest part of the job; well, the second-hardest part is the monotony. The third-hardest is the long hours upright. Standing at the line all day will get you acquainted with every last bone in your feet, and you’ll wonder how they’ve held you up as long as they have. Everything Inc. advertises that the employees are the bones of the organization. The employees like to say: “sure, they walk all over us without even knowing it.” Well, if they walked on my foot-bones, they’d know it.

“At least my job is stimulating,” Dan said one morning on the line.

We all looked queerly at him, like what the hell is he going on about now? Dan touched the alligator clip to his nipple and feigned electrocution, earning a couple snorts of amusement up and down the line. He’d never let it stay quiet for too long without cracking some sort of joke. On an assembly line, humor is always worth the effort. Orwell said it best: “Every joke is a tiny revolution.” And since that was all the revolution we could manage, every snicker was a little badge of victory.

Dan had told me that day outside of Placement: being a slave is one thing, but being a slave alone is the pits. It was true; sure, we were working, but with the guys around to bullshit with, life in the trenches could be tolerable. The line was our own little social club, and we made the best of it that we could. We were all there because we had to be, but that was no reason not to enjoy the company.

As for hive-life, Dan kept pushing beers through the wall, and I sure as hell kept pulling them out. I felt bad sometimes that the other guys couldn’t be there with us. Even if they’d been in adjacent rooms, their closets would have been facing in the other directions. It was luck that Dan and I had ended up with our closets staggered together the way they were. I did feel lucky, but I resented the fact that the other guys couldn’t be part of it.

“I’ve heard the Japanese sleep in drawers,” said Dan. “At least we get to sleep in prison cells. Could be worse, ya know.”

I’d cleaned up the dust from the sheetrock and hung a little picture over the hole for good measure. Now, with Dan in his closet feeding me beers, the closet was like the little arcade-nook back at the Drug Fair of my childhood. It was the new, happening place to be.

“Gets you to work on time,” I said. “With the rooms so small, you can’t wait to get out of here in the morning. Even if it’s just to stand on the line all day.”

“I’d like to get out right now,” Dan said. “Go prowl the streets. Screw up the uniformity.” I heard the grin in his voice.

“That homeless guy you pointed to,” I said. “On the bus. How did he manage to sneak out at night like you said?”

“Dave? He bribed his way around, same as I do to get these beers up here. Only he pushed his luck.” His chair creaked. “Think about it. A few bucks here, a six-pack there; you can get people to turn their heads the other way, but once you start making noise, the stakes are raised. They want bigger bribes, you ask for bigger favors, and before you know it, the system’s broke, and you’re more trouble than you’re worth. I don’t know for sure, but I’d bet some of those guards moved to get Dave caught, maybe got him nabbed out on the street like he’d never signed back in. Only a guess though.”

“And you thought he might’ve died?”

“Died? Why’s that?”

“You said something like you were glad he was still above ground.”

“No, no, that’s not what I meant. I meant I was glad to see he was up on the street. Some of those channel rats never come up at all.”

“Channel rats?”

“The channels, underground. Old flood channels down there, some kind of drainage system. That’s where the old hobos squat to keep away from the cops. I’ve heard the real crazies never come out at all. So Dave might be homeless, and guaranteed he’s still the same crazy bastard, but at least he still comes up for his Vitamin D.”

“No kidding. How many people live down there?”

“Underground? Who knows?” He took a few long gulps. “He could’ve died too, I suppose, those bad habits’ll get you eventually. And Vitamin D deficiency.” his chair squeaked. “You know these studs are near twenty inches apart?” he said.

“What’s that?”

“The wall studs,” he said. I heard him knocking at the wall.

“Well, the place is still standing, isn’t it?”

“Nah, that ain’t what I’m getting at. I’m thinking I could cut a whole doorway here. Imagine how much more comfortable it’d be with a nice little doorway.”

“Sure would,” I said, chuckling.

“Nah, I’m serious.”

“What?”

“Yeah, seriously.”

That anxious feeling crept back into my stomach. “No, come on. There’s no way we could get away with that, that’s crazy.”

“Starting to believe quite the opposite, little doggie. I say a hole’s as good as a door and a door’s as good as a hole.”

“Fair enough,” I said. “But there’s no way that—”

Before I could finish my sentence, a drywall saw was poking through the hole. Then it was sawing sideways.

“Dammit, Dan…” There was no stopping him. Enough beer in the guy, and Dan was a freight train.

“You crazy bastard, where the hell did you get a saw?”

I got up and listened at the door, shaking my head. Is he really doing this?

When he had finished, there was a narrow opening between our rooms, cut to the metal studs. And there he was, standing in his underwear.

“Christ.”

“Now ain’t that nice?” he said, admiring his work. He coughed.

I realized I had sweat right through my shirt. “You’re out of your mind, Dan… If you get us in—”

“There’s no way for ‘em to know. The closets are our business, doggie. Looks like we got one over on ‘em after all.” The look of pleasure on his face was disarming. If I was appalled, the emotion was impossible to hang on to for long. Maybe we had gotten one over. And besides, what was done was done.

“And what the hell are we supposed to do with all this wallboard?”

Dan broke his sheet over his knee into two pieces and dropped them into the rectangular hole between our floors. They fell a story and landed on whatever brace was between the studs. I winced at the impact.

“Downstairs is the night shift,” he said. “No one there to hear it.”

I took a deep breath. He was right, there was no one down there this time of night. I broke my side of the wall in two pieces and dropped them down the hole as well. I felt a cool waft of the trapped air ride up between the walls.

“Well, come on in,” Dan said. “Sorry, I wasn’t dressed for company.”

Sometimes we’d hang out in his room, sometimes in mine, always a case of beer between our swivel chairs, which we’d carry room-to-room like briefcases. Dan’s room was a mirror-image of mine, but you could tell the difference by the condition he kept it in. His suitcase sat half-unpacked; he’d only taken out a few shirts, a stack of his novels, and this little “go-bag,” as he called it. It was a bag of emergency stuff, just in case he got himself in a bad situation he needed to get out of quickly. A flashlight, various tools, and his favorite toy: a locksmith’s pick-tool. A “lock-gun,” he called it. “Some people call it a lock-out tool, but I think of it as more of a break-in tool, doggie.”

I’d tease him about the go-bag, but he was unflappable in its defense. “You should have one too” he’d tell me. It seemed the hallmark of the chronic troublemaker, and that, he’d certainly proven to be.

Once he’d drank enough, he’d invariably bring up his discarded literary ambitions, sometimes with humor, more often with undertones of regret. He never told me just why he’d given up writing in the first place, only that it had been a kind of “bad habit” for him. Things just hadn’t worked out the way they were supposed to have, I supposed. I supposed they hadn’t for anyone around here.

I’d still have the occasional twinge of loneliness from time to time; this lingering grip of regret for all I’d left behind. The precious and the broken alike. But just the same, I’d have occasional twinges of thankfulness. It wasn’t so bad, relatively speaking. I wasn’t alone, not altogether so. Not at all, actually. I’d been more alone on the outside, at least since the enchilada went ahead and fell apart. And I wasn’t the failure I’d been on the outside, not necessarily. Not anymore. Not here.

Failure. When I was a kid, the big thing at all the fast food places was the dollar menu. Once the meat was all but plastic, all the burger joints could do to stay competitive was to drop the prices to a buck. A patty of who-knew-what, a pickle, a dollop of ketchup and a bun. One dollar.

I remember thinking that no matter how bad things got, you could never starve in this country. If your kids were hungry, you could take them to McDonald’s and feed them for pennies. You could sit in one of those colorful plastic booths and eat dinner with them, and they’d enjoy it too. And you wouldn’t be a failure, not that night; at least you wouldn’t seem like one. You might know deep down that you were good for nothing, but the kids wouldn’t know it. At the time, it was a comfort to me. If only that were all it took to keep a family together. A few burgers and my own goodwill.

Dan was already out and about by the time I woke up on Saturday. He’d planned to sit out in the park area and read his sci-fi anthology until the sun went down. “Tanking up,” he called it. “To keep the brains flexible.” God knew, we didn’t flex our brains too hard during the week. I thought I ought to start reading again too, maybe not all day, but a little here and there, just to keep my own brains flexible. But first, I needed to pick up some provisions.

The cafeteria was closed on weekends, so I bought a can of coffee from the vending machine in the lobby for two credits and checked out at the front desk and hit the street.

I recognized a couple of people from my floor on the way to the markets and I waved hello. They waved back tentatively, checking around for security and uniformity officers who might deem the gesture suspicious. All around, an air of quiet complacency seemed to keep everyone facing strictly forward. As I walked, I felt this sensation of boredom; not my own boredom, but this looming fog of malaise. The uniformity, the security, it seemed to infect everyone and everything. A little black bird landed to peck at a crumple of paper on the sidewalk, then flew away again, apropos of nothing.

Uniformly arranged rows of shelving at the market. Everything Inc. used this drab packaging that left the boxes of food difficult to identify without seeing the pictures up close. Boxes of macaroni with their packets of powdered cheese seemed popular; a whole row dedicated to what I’d heard called “Kraft dinners,” disheveled on the shelves. I took two, four credits apiece. I had about 100 credits I could spend without breaking my budget for the week.

I picked up a carton of milk, a box of cereal, granola bars, dried apples, cheese, bread and eggs. I thought my basket looked pretty pathetic, so I went back and took a couple more Kraft dinners. On the way to the register, I grabbed a tin of instant coffee. My bill came out just under budget. I left with my backpack full of provisions and continued on my walk around the square.

There was a bookstore. I hadn’t seen one of them in a long time. Remembering my promise to start reading again, I wove through the crowd to get there. Inside, the selection was sparse. As far as fiction was concerned, the shelves were dominated by the classics, re-published by Everything Press in bland, uniform covers. All paperback. I tilted out a copy of Moby Dick, a book I’d never finished, but had always planned to read again. I checked the price on the back cover—ten credits. I read the first few paragraphs with this strange sense of guilt I didn’t understand right away. I looked around the bookstore; there were only four other patrons. Just the five of us, hiding between the shelves, taking secretive little peeks into books. Maybe it was the idea of peeking into a world outside the institutional greys and whites of Enterprise, where uniformity fell only into the structures of paragraphs and pages. The guilt was that of attempting an escape. I took the book to the register and presented my card, somehow harboring this illogical notion that I would be caught doing it.

On the way back to the building, my copy of Moby Dick hidden securely in my backpack, I planned to cook a box of macaroni and cheese using two of the paltry cheese packets; one from the original box, and one from another. Along with my new novel, two traitorous acts against the status quo. But before I turned back to the building, I thought I’d take a walk around the rest of the hive, just to have a look around.

The residential district was comprised of a number of massive buildings just like mine, roughly the same shape and size. Likely the same number of units—4,400 of them each—although it was impossible to know for sure. I counted eight buildings on my walk back and tried doing the math in my head. That was 4,400 x 8. 32,320 units for the employees at Everything Inc. I’d heard there were 50,000, but there couldn’t have been that many units in the hive. 35,000 maximum, I figured, and even that was pushing it. Maybe there was another residential area in an area of town I hadn’t seen. There would have to have been.

I’d have liked to do some more exploration, but with only one day off a week, and as tired as I was on that day, there wasn’t a whole lot of opportunity to snoop around. I was curious about the power plant on the west side of town. What was so secretive about it? I wanted to take a walk around it, not to try and get inside or anything, only to walk the perimeter. Only to know whatever it was that they didn’t want me to know. Dan did enough sneaking around himself, didn’t he? I was tired of being a sucker. I ought to be a little more like Dan, I thought.

My feet had mercifully begun to adjust to all the standing, so I decided to walk back to the hive one day after work. If I kept a brisk pace, I should have no trouble getting back before curfew.

The daytime heat was lifting quickly, bringing behind it the dry, uninsulated desert cold. The crenelated shadows of the hive buildings stretched across the asphalt in the moonlight like the teeth of a giant beast. 4,400 units each. Dim little lights in all the tiny prison windows. I was reminded again how there only could have been 35,200 units, and wondered again how there could possibly be 50,000 employees in only that amount of space. Something about it was unsettling. It shouldn’t have been; I was sure there was a perfectly good explanation for it, but it continued to eat at me.

Dan was already good and buzzed by the time I got back. I thought of bringing up the employee conundrum, but he had his own dilemma he wanted to talk about.

He polished off his beer in just a couple of swigs. “I wanted to be a writer. Have I told you that, doggie?” He belched loudly.

“Yeah, you told me.”

Some of the books I’d seen in his room were about writers. A Moveable Feast by Hemingway, On Writing by Stephen King, that kind of stuff. Even if he’d never brought it up, I’d have figured he probably picked up a pen himself at one point or another.

He reached for another beer and snapped off the cap and promptly drank down half the bottle. “Writing. That was my only ever bad habit.” He belched again.

“That was it, huh?”

“I’d think up stories while I was working and sit down after dinner and type ‘em out. Debbie hated it, she wanted me to watch her shows with her.”

“What kind of stuff did you write?”

“Eh, I don’t know. Wrote this one story where this kid, this kid that gets picked on a lot in school, he’s walking home one day, and there’s this old toilet perched on someone’s curb, waiting to be picked up by the garbage man, you know?”

I nodded.

“Yeah, well… So the kid’s walking by, and he hears something funny. And he turns to look, but it’s just the toilet bowl standing there. So he starts to walk again, but he hears the noise, and he turns to look, and there’s the toilet with the lid moving up and down. So he goes closer…”

“Yeah…”

“And closer… And the lid lifts up a little and the toilet goes ‘Randy,’ because that’s the kid’s name, ‘Randy, I know what they say to you. I know what they do to you at school. And I know how to make them stop.’ and Randy, the kid, he thinks he’s seeing things, right?”

“Right…”

Dan took a long swig. “So Randy leans closer to the old toilet bowl. He goes: ‘I’ve lost my mind.’ And the toilet bowl says, ‘I am Flushtor from the planet…’ well, I forget what the planet was called, but the point is, it’s not a toilet. It’s an alien. It just looks exactly like a toilet. The whole race looks like toilets.”

“Should’ve been Planet Porcelain,” I said.

Dan grinned and took another swig. “That’s ridiculous, Pauly, it would’ve made the whole thing unbelievable. Anyway, the aliens are telepathic, so it was able to read Randy’s thoughts, you know? So it teaches him how to overthrow the bullies at school and everything. You get the idea.”

“I love it.”

“Eh…” Dan finished his beer and dangled the bottle off the side of the chair. “I quit all that, I told you, it was a bad habit.”

“Why do you keep saying that?”

“… The whole time I was sitting there writing, I never considered why the hell I was doing it. The minute I did, I realized I had no answer. Debbie was right, I was crazy. Because there was no real reason to do what I was doing. No one was ever going to buy it or print it or anything. No one even read stories anymore. So when I really asked myself why, the only real answer I could come up with was that I was amusing myself.” He held up his hands as if to say he didn’t know. “So here we are, the wife and I, sitting in separate rooms and I’m just amusing myself. It’s masturbation, is what it is.”

“You know Moby Dick wasn’t regarded as a great book until after Melville died.”

“Sure, I know that. Not sure why, but…”

“Things change. The book didn’t change, everyone else did. Suddenly, Moby Dick is a masterpiece.”

Dan nodded for a moment. “So what’re you gettin’ at, doggie?”

“Well maybe you thought you were just amusing yourself, but what if you were doing something bigger than that?” I polished off my beer and slipped the bottle into an empty six-pack. “Maybe Mellville’s old lady told him he was wasting his time when the critics started shitting on him. But her opinion isn’t so important now, is it?”

He grinned, staring glassily into space for a second. “So you’re saying Flushtor could’ve been the next Moby Dick?”

“Well, it could’ve been something.”

He considered it a minute.

“So you’re saying I should give it another go?”

“Shit, I’ll read it.”

That seemed to bring his eyes into focus. Some glimmer of something that wasn’t there before. It may have actually sobered him up a bit.

“I don’t know, Pauly. I haven’t had much luck with second tries.”

“I haven’t had much luck with anything,” I said. “But whatever you’re chasing…”

He grinned. “You’re smarter than you look, you know that, Paulo?”

At a quarter past midnight, well-past the time when all the day-shift guys were supposed to be sleeping, two sets of Everything-issued boots began their tapdance down the hallway. Dan and I met eyes; it wasn’t unusual to hear the boots stepping down the hall late at night, but there seemed to be purpose in these steps, not the leisurely pace they normally took, but like a couple of fish flopping on the floor of a boat. And then they stopped. Right in front of my door.

Knock knock knock. “Mister Harper?”

I motioned for Dan to hurry back to his room, but he didn’t move. He only sat there grinning.

“Mister Harper, we have the right to open this door without your permission. So you could either do it, or we’ll do it for you.”

I glared at Dan, still unmoving, only grinning back at me. What was he thinking? Were the officers bluffing? If they opened the door and saw us both in here, we’d be in trouble. We could be launched right out into the street, he understood that, didn’t he? The old sentiment flitted through my mind; that inevitable conclusion, wherein my mind, all paths seemed to lead. Was I about to become a failure? Again?

It was too late.

The door opened. Two of the sharply-dressed officers stood in the doorway, wide-eyed at the scene. “You’re in violation of Code Ten,” one said.

“And Thirteen,” said the other, eyeing the empty beer bottles.

“Yeah,” said Dan. “I suppose you’re right.”

I had no reply. There was no defending ourselves; we’d willingly broken the bylaws, and now we were in trouble. But Dan seemed calm as ever.

The officers looked queerly at each other. Neither of them paid attention to the closet. They only knew that Dan had illegally left his own room and I’d let him in mine.

“You’ll both be fined a full week’s credits in accordance with the Hive Bylaws. Further violations will result in steeper penalties. A second violation will result in—”

“You get paid commission for handing out fines?” Dan asked.

The officers looked confused. “We’re salary,” one said, “same as everyone else.”

“So what do you have to gain by fining good guys like us besides bad karma? I’ll tell you what, how about a little gratuity for a job well done…”

Dan pulled out his wallet. “Off the books,” he said, and took out a fifty-dollar bill. They seemed staggered by just the sight of it. I must have too. The officer that had spoken looked at the other officer. He nodded.

“Of course the real reward is being good to your fellow man,” Dan said.

Silently, the officer held out his hand.

The officers left, fifty dollars richer. Tax-free money. The kind you could stuff under your mattress.

It was a minute before I had my nerves settled enough to talk. I couldn’t believe he’d had the balls to do what he’d done. Granted, I might have felt differently if it hadn’t worked, but it had.

“Where did you get the cash?” I asked him.

“I’ve been hanging on to that bill,” Dan said. “You gotta get the officers good and filthy if you want to stretch out a little.” He linked his fingers through his long hair and put his boots up on my end table. “Like a hunter. Gotta wait for the perfect moment to strike.”

The fifty had marked them like a cattle prod, Dan explained; certified corrupt. We’d forged an agreement, the four of us, and we all had each other by the balls. It couldn’t be allowed to escalate, he told me, not like it had for Dave. But as long as we kept quiet, they’d keep quiet too.

“What if they come back looking for more?” I asked.

“You know what kind of jobs are reserved for dirty law-enforcement?” There was a satisfied smirk on his face. “Let ‘em come back looking for more. They’d sooner dig up a turnip.”

I would sooner dig up a turnip than explain the mixture of feelings going through my head at that moment. I knew how I wanted to feel; I wanted to be thankful. I wanted to high-five Dan for a job well-done. But how I really felt was more complicated than that. It was so clear to me at that moment that I’d never have been able to do it by myself. How never in my life had I been able to open my mouth and make anything notable happen, let alone urge anyone in a particular direction. And as thankful as I was to have the officers off our backs, I wished I could have made it happen myself, or at least helped. I just wasn’t made of the same stuff Dan was. And that’s why I’d been a failure. That’s why I hadn’t even opened my mouth as I saw my family slipping away. If only I’d been made of different stuff, maybe everything would have been different. Maybe Dr. Thurmond’s money wouldn’t even have mattered to us.

“There’s always a weakness, doggie.”

The powers-that-be at Everything Inc. offered a constant flow of opposing force to us workers, like a tolerable storm whose winds never died down. While Dan and I did our best to make our stay as comfortable as possible, there were always new rules, always stricter guidelines, and they never seemed to be for any necessary reason. It was like they only wanted to make it more difficult not to get in trouble.

You always had the feeling you were being watched. Maybe not literally watched, but monitored somehow. They seemed to know when you were at home, know when you’re sleeping, know when you’re up. The television would just pop on by itself when there was something they wanted you to see. That’s how I learned about the new “Performance Policy Amendment” one morning.

The face on the screen was our benevolent president, Len Carter, smiling that precarious smile of his. Always seeming to teeter between personalities. Dan had explained to me that the people behind those smiles were always dangerous. “Bit like a gator gar,” he’d said. And if he hadn’t told me that, it never would have occurred to me, naive as I was.

“As employees of Everything Incorporated, you are entitled to be informed of all policy updates. Regarding our performance policy, a few minor updates have been instituted to preserve and maintain the quality of our products and services. To pre-frame these adjustments, I’ll restate that at Everything Inc., our model is to never ask too much of our employees. All of our jobs are designed to be easily performable by anyone of any age or gender, given proper training. It is our strict policy never to ask too much of our workers, and to provide the means and materials to offer a reasonable day’s work. If for any reason an employee is unable to work with reasonable expectations, adjustments may be made, or a transfer to another job may be completed. If you feel that you qualify for an adjustment or transfer, ask your supervisor. Otherwise, an employee chronically un-productive will be administered a series of strikes. Once an employee reaches his or her third strike, he or she will be rejected from his or her position and his or her lodging will then be forfeit. That is all.”

I knew Dan was probably seeing the same thing next door. I wondered what he thought of it. Vague enough, yet deliberate enough to seem both innocuous and threatening at once, like a tornado watch in an unlikely place. But with the tension at Everything Inc. seeming to stiffen all of a sudden, you got this feeling like there was an axe falling, ever so slowly, over all us slaving losers. Reinforcing the notion was my quiet suspicion that there wasn’t quite the number of employees at Everything Inc. as advertised. There just wasn’t enough room, and with all the new people constantly coming in, there must be an increasing pressure to get the old ones out. I sounded conspiratorial to myself, but I was also tired of being so naive. It seemed to me that the hurdle for acceptable production was slowly being raised. It would have to be.

“How many employees does Everything have here?” I asked Jack, already knowing what his answer would be.

“50,000 on average,” he said.

“I told you that already,” said Dan.

“But do they all live in the hive? Is there any other residential area in Enterprise?”

“Nah,” said Ronnie. “They’re strict about that. They like to know where everyone’s at.”

“That’s how they keep their thumb on top of you,” Jack affirmed.

“I was thinking about it. There’s just no way 50,000 people live in the hive.”

“On average,” said Ronnie. “People come and go. This ain’t for everyone, ya know.”

“My building has 4,400 units. If all the buildings are like mine, that’s eight buildings with 4,400 units. That’s 35,200, maximum. So where are all the rest?”

“Hell,” Ronnie said. “If I was any good at math, you think I’d be here?”

“Hell yeah, you would,” said Jack.

“I’m just curious,” I said. “Doesn’t make sense.”

“Maybe there’re more units in some of the other buildings,” Dan said. “Ronnie, what building are you in?”

“Four,” said Ronnie.

“Alright,” I said. “So when you go home later, have a look at the chart in the stairwell. You should be able to figure it out.”

“What about that plant?” Dan said. “Supposed to be exclusive people working the plant. Maybe they live somewhere else?”

“Could be,” I said. “But not 14,800 of them.”

“I live in building six,” said Jack. “I’ll check my chart too.”

“If it turns out the buildings are the same,” Dan went on, “You’re right, Pauly. That’s a little strange.”

“Any of ‘em shack up in the same room?” asked Jack.

“No way,” said Ronnie. “Against the bylaws, one man per-room. Don’t need any of us working idiots coming up with conspiracies and shaking things up.”

I got the knock a little later than usual that night. By now, I’d been conditioned like a lab rat to get my beer on time. Not the healthiest habit, but hey, I breathed plastic fumes all day long. If something was going to do me in they’d find my lungs turned to Tupperware before they worried about my liver. Classic rationalization, Paul Harper. I got up and unlocked the closet door.

“Where you been, Dan?”

Dan had stayed behind after work. I knew he was going to get beer in any case; still, he usually got back a lot earlier than this.

“Scribbling a little bit.”

“Writing?”

He sat down and handed me a beer and opened one himself. He looked like he’d had a couple already. “This whole place. It’s not really the rules themselves that bother me, it’s the restrictions you put on yourself to deal with them. You know what I mean?”

“Not really,” I said.

He sighed, took a drink. “You get up and go to work, work all day, then come home and go to bed. It’s the mindset you have to put yourself in to live like this. It costs more than just your pride. You gotta give up your aspirations, your expectations, your creativity. Because how could you live with those things? You can’t take care of ‘em. You can’t feed ‘em. They’d end up dying like neglected pets.”

I nodded. “They kind of own you.”

“Well I can’t do it doggie.” He chugged his whole beer and belched. “I remember Debbie telling me I was crazy for writing my stories, and that day I decided she was right. I guessed there was no point in writing my stories, fine. But what was the point in anything? Getting up, working, breaking even at best. What’s the point? There was no point. I was writing because I liked to.”

“Seems like a good enough reason to me.”

“No reason. You know how you’re doing what you’re supposed to do, Paulie? Because you’re doing it for no reason. Because there’s no point to it. Like breathing.”

“Pretty sure there’s a point to breathing,” I said.

“Bad example. You know what I mean.”

I did. I must’ve looked confused for a second because I was wondering what exactly it was for me; what did I enjoy? What did I do for no reason. “I get it,” I said.

“So you wanna read it?”

“Your story? Yeah, absolutely.”

He set down his beer and went through the closet into his room and came back with a short stack of paper and handed it to me. I took it. At the top of the first page it said: Flushtor: The John From Space

“I’ll read it right now if you let me.”

“I got my beer,” he said. “Have at it.”

So I read it. It was better than I thought it would be. Sure, it was loaded with puns—I never figured an alien would be such a potty mouth—but just like Dan, it was a good time and funny as hell. I enjoyed it. It wasn’t until later that I admitted to myself that I enjoyed it more than most of Moby Dick. And even later that I realized why I’d stopped reading like I used to in the first place.

It had been sometime during that period between when money meant something, and then suddenly didn’t. This period of dissipating novelty during which the cement and aggregate of life turns everything concrete. Imagination becomes kidstuff. Years go by. You lose things. You think you’re moving forward, but inevitably, you lose more than you gain.

I was lying in bed when that thought came to me; word by word, like a line of moving prose. My eyes opened wide, staring up at the darkness.

After doing my errands on Saturday, I thought I’d explore Enterprise a little more. On the far side of town I found an Internet cafe, something I’d heard about from the guys on the line. In the outside world, Internet cafes were things of the past, long-extinct since the Web became so mainstream. But here, without any signals not Everything’s own, access to the Internet was exclusive and strictly limited. By the time I went in and sat down in front of a computer, I’d forgotten all the things I wanted to look up. What I remembered was that anything I browsed would be tied directly to my account, so I’d have to be careful not to type in anything that made me appear suspicious or traitorous. Big brother was always watching.

But what harm was there in being interested in the company I worked for? I typed in “Enterprise power plant.” What I found didn’t seem particularly curious or secretive.

Enterprise was largely powered by gas, including the electricity, also generated by gas; highly advanced technology developed by Everything Energy, an Everything company; completely self-sufficient. All I could dig up about the technology was that it had its roots in old landfill methane-extraction. Some of this I’d known already; you could see all the garbage trucks in town carrying loads of waste to the plant for composting. Big deal. So what was the trouble with letting people work there? To protect the top-secret technology?

Just out of curiosity, I typed in “methane gas energy technology,” expecting to see some giant deposit under Nevada, but there wasn’t one. Could it be that all the methane came from a landfill? All of Enterprise’s garbage?

By the time I asked myself that question, I had used eighteen credits-worth of Internet. It wasn’t worth it. With the Internet so prohibitively expensive, if there was something you needed to research, you’d better know exactly what it is. Surfing just isn’t worth the money.

On my way back to the hive, the midday blaze was losing its strength. I saw a black man walking east, swinging a plastic bread bag at his side as he went. His clothes said he was homeless. And then I recognized him. It was Dave, the fellow Dan had recognized on the way in. I crossed the street and walked alongside him.

“Dave?” I asked.

He looked queerly at me. “Do I know you?”

“No, actually. I know Dan. Guy who used to work with you stamping product. Southern accent?”

“Dan… With the accent, yeah, I remember him. Is he back?”

“Yeah, he’s back. We live next to each other.”

He chuckled. “Man, I thought he’d end up on the street with us.”

“He’s something,” I said. “He said you’re something too.”

“Yeah, I’m something. You tell him I said he’s something else.”

“Want a cup of coffee?”

He bent an eyebrow at me. “You buying?”

“Yeah, I’ve got a couple credits left.”

“You’re buying, I’m your man,” he said.

We sat at a bench outside a coffee shop on the corner of the intersection. Make a right, and you’re headed back to the hive. Left, and you’re headed towards the outskirts of town, near the gates back out to the outside world.

“I heard what happened,” I said. “With the fines and everything.”

“One fine was enough for me. I barely had enough to get by as it was. Add my lifestyle, and well… I don’t know if you’ve ever had any expensive lifestyle habits, but if you do, you know they take precedence over all that other stuff. Bills, rent, all that.”

He didn’t seem crazy to me, not the way Dan had described him. “I can imagine,” I said. “So the fine was enough to—”

“To put me out on the street, which was the whole reason I came here, to get off of the street. Well, at least I was used to it.”

“I heard a lot of you guys live down in the flood channels.”

“I squat down there most nights. I’m no channel rat though, I come up during the day. You gotta be careful not to get too comfortable down there. They’re wise to it, the law enforcement. They know we’re down there. And if they think you’re a troublemaker, they’ll snatch you up and drag you away. And we never see those channel rats again.”

I was stunned. “You mean they go down there and just drag you guys out?”

“They say it’s in the interest of public safety that we can’t be down there, interfering with the utilities and all that. And we never do anything like that, we just need a place to sleep.”

“They’re utility tunnels?”

“Go from there,” he pointed back towards the opening of the tunnels “all the way out to the power plant. But we ain’t messin’ with no utility workers or no utilities. We just wanna live. We don’t want any part of that meat grinder you workin’ in.”

“It’s not so bad,” I said.

“See, you might not think it is, because you’ve got a little roof over your head and Everything brand eggs every morning, but I assure you. It’s bad. It’s worse than you know, and you’re gonna find out.”

“How so?” I asked.

“Every credit they give you, it all goes right back to them. The rent, the food.” He holds up his paltry bag of bread. “They give you a handful of credits, and you spend it all on their stuff for a profit. What they give you is nothing. What you give them is labor. It’s free labor. Know another word for that, Paul?”

“I uh…”

“Slavery. That’s the word you wanted to say. So ask yourself. Does this arrangement really feel fair to you? Having to live under their rules? Having to buy all of their goods. Just giving back all the credits you earn as a mere formality of the process you’re really in? Slavery.”